How War Changes the Human Mind

War changes everything — the world, the people, and most deeply, the human mind. The effects of war on the human mind go far beyond the battlefield, leaving silent wounds that shape emotions, behavior, and even identity. Soldiers return home with invisible battles still raging inside them, while civilians carry memories of loss and fear that never fade. Understanding how war impacts the mind helps us see that peace is not just the absence of war — it’s the healing of hearts and thoughts scarred by it.

Immediate Psychological Trauma from Combat

Exposure

Understanding Acute Stress Reactions in Battlefield Conditions

Combat doesn’t just test your body—it hits your mind hard, too. Even the toughest soldiers can feel completely overwhelmed out there. The brain reacts fast and intensely to the chaos of battle, and it’s nothing like what people go through back home. It’s this constant mix of danger, split-second choices, and violence that really cranks up the pressure.

Everything about the battlefield screams overload. The noise, the blasts, the confusion—it’s nonstop. You’re always aware that things can go sideways in a flash. Add in no sleep, brutal weather, and seeing friends get hurt or worse, and it all piles on. The mind can only take so much. Sometimes it just shuts down for a bit, or swings the other way and stays on high alert, even when things calm down. And honestly, those effects don’t just disappear once the shooting stops.

Spotting Signs of Combat Shock and Dissociation

Combat shock comes on fast and hits hard, both in the mind and body. People on the ground—whether they’re soldiers or medics—need to catch these signs right away. The most obvious red flags? Trembling or shaking you just can’t stop. Heart pounding and breathing way too fast. Sometimes you break out in a heavy sweat, even when it’s not hot. There’s often a wave of nausea or an upset stomach. Muscles get tight, and headaches show up out of nowhere. These reactions are your body’s alarm bells—don’t ignore them.

Psychological Signs:

You might feel numb or cut off from what’s happening around you. Sometimes, it’s just hard to think straight or make choices. Maybe there are blank spots in your memory, or you can’t remember what just happened. Fear hits hard—sometimes it’s full-blown panic. There are moments when everything seems fake, like you’re not really there.

Dissociation is the mind’s way of trying to protect itself when things get too intense. Soldiers often talk about feeling like they’re outside their own body, just watching things happen, or like everything’s part of a strange dream. This mental escape can help in the short term, but it gets in the way when you need to stay sharp and make quick decisions.

How Adrenaline and Survival Instincts Reshape Brain Function

War flips a switch in the brain. Adrenaline starts pumping, and suddenly, everything feels sharper and more urgent. The adrenal glands pump out epinephrine and cortisol, cranking up awareness and turning the body into a machine built for survival. In that moment, nothing else matters. Your body dials down things like digestion or even deep thinking, just so you can react in a split second.

When survival kicks in, the brain changes how it works. Instead of carefully weighing options, it shifts gears. The prefrontal cortex—the part that helps you think rationally or consider right and wrong—takes a back seat. The amygdala, which handles threat detection and raw emotion, takes over. That’s why some soldiers pull off incredible feats in battle but then have trouble with simple decisions or remembering things.

Here’s the thing: the more this happens, the more the brain adapts. After enough adrenaline surges, the brain gets used to scanning for danger, ready to sound the alarm at the slightest hint of a threat. This was useful in combat, but it doesn’t turn off easily. So when soldiers come home, their brains still jump at loud noises or tense up in crowded places. It’s not just habit—it’s the brain, rewired by survival.

Breaking Down the Fight-or-Flight Response in War Zones

In war zones, the fight-or-flight response isn’t just a quick jolt of adrenaline—it’s on overdrive. Soldiers bounce between fighting and fleeing, sometimes in the same moment. Civilian emergencies? They usually come and go. War is different. The stress just keeps coming, day after day.

Here’s what “fight” looks like in combat:

- Soldiers get aggressive—no hesitation, just action.

- Pain takes a back seat. People push through injuries they’d never ignore at home.

- Bodies move faster and hit harder. You’re suddenly stronger, quicker.

- Focus narrows. Everything else fades except the threat right in front of you.

- Some injuries even go unnoticed until the adrenaline fades.

Now, “flight” in a war zone isn’t just running away. It’s smart, fast, and calculated:

- Decisions about retreat happen in a split second.

- Suddenly, you notice every exit, every bit of cover—your mind maps escape routes on the fly.

- People can run farther and faster than they ever thought possible.

- You’re constantly weighing the landscape—where to hide, where to run, what might keep you alive.

The Freeze Response:

You feel stuck, frozen in place when things get too intense. Even when you know there’s danger, your body just won’t move. Sometimes it’s like you’re not even in the room anymore—everything feels far away. And when someone tells you to do something, you just can’t react fast enough.

A lot of combat veterans pick up another habit, too—the “fawn” reaction. Instead of fighting or fleeing, they go out of their way to keep authority figures happy or sidestep any kind of conflict. It works in the military, where following orders can literally save your life. But once they’re back home, that same pattern can make things tough with friends, family, or at work.

When your body keeps flipping into these stress modes again and again, your nervous system actually changes. The impact sticks with you long after the battlefield is gone.

Long-term Mental Health Consequences of Warfare

Developing post-traumatic stress disorder from war experiences

Combat veterans deal with PTSD way more often than the general public—about 23% more likely, actually. The stuff they see and live through in war sticks with them. It’s not just the danger or violence, but also those moments that tear at your sense of right and wrong. These experiences leave wounds you can’t see, and they don’t just disappear once the fighting stops.

Memories sneak up on them. Out of nowhere, the smell of diesel can yank them back to a convoy under attack. The chop of a helicopter’s blades might set off a flood of memories about frantic evacuations. It’s like their minds are always on guard, even when they’re safe at home.

PTSD usually shows up in patterns. Most veterans start seeing symptoms within three months of coming home, but sometimes it takes years before it really hits. Sleep? Almost impossible. Their brains are stuck in survival mode, and nightmares replay the worst moments over and over. After a while, just the thought of closing their eyes can feel terrifying.

Many veterans talk about feeling completely out of place in their own lives. Stuff they used to love doesn’t matter anymore. That emotional high from deployment gets replaced by nothingness. They stay on edge, always scanning for threats. Instead of helping, that vigilance makes it hard to relax or feel safe—even in their own homes.

There’s help out there. Treatments like cognitive processing therapy and EMDR give hope, but recovery takes time and serious support from professionals. Family matters too. They often notice the signs first and push for help, but they need support themselves. PTSD isn’t easy, and everyone close to it gets pulled in.

Managing chronic anxiety and hypervigilance after combat

Living with chronic anxiety and hypervigilance after combat isn’t just tough—it seeps into every corner of daily life. In war zones, staying on high alert keeps you alive. But back home? That same instinct just won’t shut off. Veterans talk about feeling wired all the time, always on edge, scanning crowds for threats that aren’t there, jumping at every little noise. It’s exhausting, both mentally and physically. You end up tired all the time, and your patience wears thin.

Even simple stuff, like buying groceries, turns into a mission. The brain treats every stranger like a possible threat, every sudden movement as a warning sign. Crowds crank the anxiety up to full blast, sometimes tipping into panic attacks. After a while, many veterans just avoid public places altogether. It’s lonely, and that loneliness only adds more weight to what they’re already carrying.

Sleep doesn’t come easy, either. It’s hard to relax when your mind refuses to let its guard down. No real rest means anxiety gets worse, and handling emotions becomes even harder. Some veterans sleep with weapons close or face the door, just in case.

There are ways to manage all this, though. Breathing exercises help calm the body’s alarm system. Progressive muscle relaxation eases some of the tension that never seems to fade. Grounding yourself with your senses—really noticing what you see, hear, smell, taste, and touch—can pull you out of spirals. Exposure therapy, slowly working up to facing stressful situations, helps too. And sometimes, medication plays a role, if a professional recommends it.

Support groups give veterans a place to open up and connect with people who really get it—no judgment, just understanding. There’s something powerful about realizing your reactions are normal responses to situations that just aren’t. It takes the edge off all that shame and self-blame anxiety likes to drag along.

Overcoming depression linked to wartime memories

Dealing with depression tied to memories of war is a whole different beast compared to what civilians go through. For veterans, it’s tangled up with trauma. Survivor’s guilt hits hard—you come back, but some of your friends don’t, and that question, “Why me?” just won’t let go. On top of that, going from the tight-knit brotherhood of the military to feeling alone in civilian life only makes things worse. Suddenly, there’s this emptiness, like you’ve lost your purpose.

A lot of veterans talk about losing their sense of self after leaving the service. The military gives you structure. You know your mission. Out here? Things aren’t so clear. The world feels unsteady, and guys who once protected others can end up feeling totally useless, stuck wondering if they matter anymore.

Wartime depression also brings something called moral injury. It’s the weight you carry when you see or do things that go against your core beliefs—or even when you couldn’t stop something terrible from happening. That guilt and shame sticks around, and honestly, regular depression treatments don’t always touch it.

To really heal, it takes more than just easing the symptoms. You have to face what’s underneath. Here’s what helps: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy tackles negative thoughts and habits—this one works well. Interpersonal Therapy builds up your relationships and communication, and that’s pretty effective too. Medication can help, but it’s a bit hit or miss. Peer support groups? Those are a lifeline for a lot of people. Just hearing, “Yeah, me too,” makes a difference.

And don’t underestimate the power of getting your body moving. Exercise floods your system with endorphins and burns off the restless energy trauma leaves behind. Some veterans find meaning again through volunteering—helping other vets or diving into community work. It brings back a sense of mission and, for a lot of folks, that’s the spark that keeps them going.

Cognitive Changes and Memory Disruption

How trauma affects memory formation and recall

War trauma flips the brain’s memory system upside down. When someone’s thrown into life-or-death situations, the amygdala—the part of the brain that screams danger—kicks into overdrive. Meanwhile, the hippocampus, which is supposed to organize and file memories away, kind of falls apart under the pressure. Instead of storing memories as clear stories, the brain grabs whatever it can—maybe a sound, a smell, a flash of color—and stashes these pieces all over the place, out of order and out of context.

Stress hormones flood the brain during combat. They jam up the normal memory-making process. So, veterans might remember the sticky feeling of blood on their hands or the exact shade of red on their uniform, but can’t piece together the full scene or what led up to it. The moments before and after just vanish, while that one detail sticks like glue.

Usually, the prefrontal cortex teams up with the hippocampus to create tidy, time-stamped memories you can replay like a movie. But trauma breaks up this partnership. Survivors get stuck with memories that don’t fade, don’t settle—they’re frozen, stubbornly vivid, and packed with emotion, even years later. When something triggers them, it’s like the moment is happening all over again.

The brain’s sense of time gets shaky too. Traumatic memories just crash through the usual filters, so the mind stays on high alert, always waiting for the next threat, even when the real danger is long gone.

Dealing with intrusive thoughts and flashbacks

Flashbacks aren’t just memories—they hit like a lightning bolt. Suddenly, your brain thinks you’re right back in the thick of it, reliving every detail. The same nerves that fired during the trauma light up again. Your heart races, your breathing gets tight, and your body snaps into fight-or-flight mode, just like it did in combat.

Intrusive thoughts are a different beast, but just as relentless. They show up out of nowhere—images, sounds, even smells that crash into your mind without warning. Sometimes, something as harmless as a car backfiring can drag a veteran straight back to a battlefield. The scent of diesel might bring military vehicles flooding back. It’s impossible to predict what will set you off next, so daily life starts to feel like you’re tiptoeing through a minefield.

To cope, the brain cranks up its defenses. Hypervigilance kicks in, so you’re always on the lookout, scanning for danger. Sure, that kept you alive in combat, but now it’s exhausting. Veterans say it’s like living with everything turned up too loud—sounds are sharper, movements seem more threatening, and your whole system stays stuck on high alert.

And then there’s sleep. Even there, you can’t escape the memories. Nightmares pull you back into the worst moments, and instead of finding relief, you wake up even more worn out. Rest doesn’t come easy—it just feels like another fight you have to get through.

Understanding concentration difficulties in war survivors

War messes with the brain’s attention system in a big way. In combat, being hyper-alert keeps you alive. But back home, that same instinct turns into a problem. Veterans end up scanning for danger that isn’t there, so even small tasks get hard. Imagine trying to read a book, but every creak or noise in your house yanks your focus away. You can’t settle down.

The prefrontal cortex—the part of your brain that handles focus and planning—takes a real beating from trauma. Stress hormones chip away at it over time. Suddenly, things that used to come easy, like following a friend’s story in a busy restaurant, become exhausting. You can’t tune out the background noise.

Working memory gets hit too. Lots of vets say it feels like their heads are full of static, or that thoughts slip away before they can finish them. Even simple chores with a couple of steps feel impossible because the brain just won’t hang on long enough to get them done. The harder you try to concentrate, the more slippery your focus becomes. It’s maddening.

And it’s not just about attention. Plenty of people feel totally wiped out, even if they haven’t done anything tough that day. Their brains are burning energy searching for threats, leaving almost nothing for regular thinking. That constant fatigue stacks up with everything else, making recovery feel even further out of reach.

Rebuilding decision-making abilities after combat stress

Combat trauma really messes with the brain’s ability to make decisions. The parts of your mind that used to handle options and consequences just get flooded by constant alertness. Veterans talk about feeling stuck, even over little things—like picking what to eat for breakfast, or deciding which way to drive to work. Choices that used to be automatic now feel huge and exhausting.

The brain’s reward system takes a hit, too. Stuff that used to feel good or motivating suddenly falls flat. It’s hard to know what you want, or what matters. That loss of direction makes even the most basic decisions stressful because there’s no clear sense of what feels right anymore.

When it comes to risk, things can go either way. Some people get super cautious—they avoid anything that might trigger old memories or cause stress. Others go the opposite direction, doing things that are dangerous, because their brain’s warning system is fried and just stops working.

Getting better means slowly learning to trust your own judgment again. It’s not about some big breakthrough; it’s about making small choices, over and over, and rebuilding confidence as you go. Therapy helps link thoughts and feelings back together, so you can start following your own instincts again. With the right support and some patience, the brain finds its way back, though sometimes you have to develop new ways of handling things in this changed mental landscape.

Social and Emotional Impact on Relationships

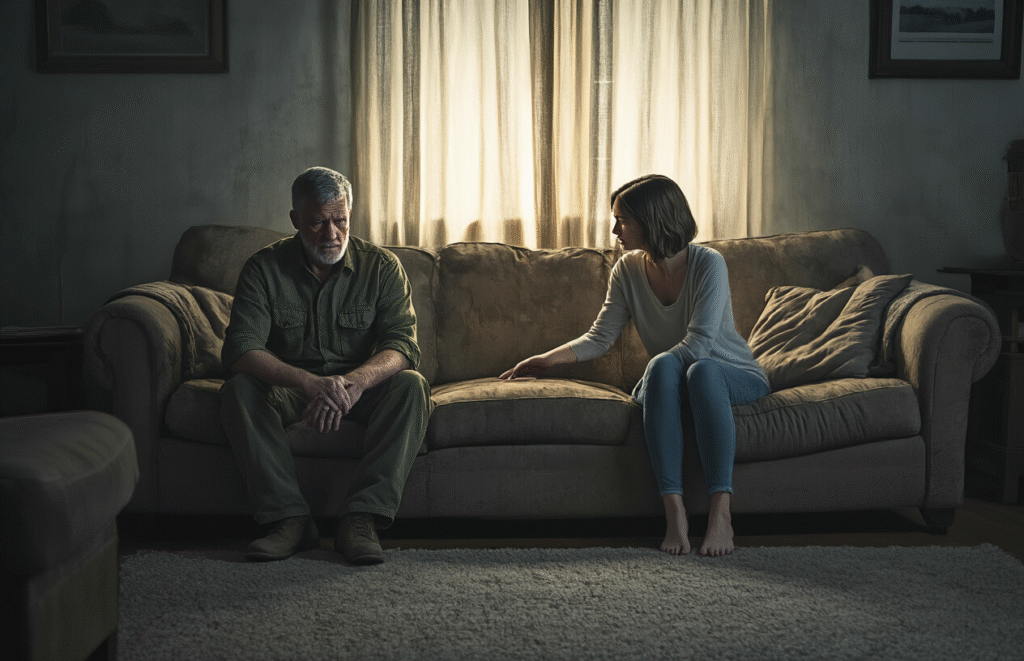

Reconnecting with family after military deployment

Coming home from war turns life upside down for a lot of families. The person who returns isn’t always the same as the one who left. They carry things inside—memories, habits, worries—that people back home just can’t see or always understand. Sometimes, you look at your spouse and realize they’re different now, almost like you’re living with a stranger who just happens to look familiar.

Those easy moments—laughing at nothing, hugging in the kitchen, chatting about your day—can suddenly feel awkward or missing. Spouses notice it first, but kids sense it too. Little ones, especially, get confused when their mom or dad seems jumpy or far away, even in the middle of family life.

But it’s not just about feelings. People who’ve served get used to being on high alert and sticking to routines. That doesn’t always mix well with the messiness of home—unexpected visitors, shopping trips, even birthday parties can feel like too much.

And then there’s talking to each other. Things shift. Everyone’s careful, watching what they say, worried about bringing up the wrong memory or causing a blowup. Even simple questions about what happened “over there” can make someone shut down. You end up with these silent walls in the house, everyone wanting to connect but not really sure how to do it without making things worse.

Managing anger and emotional numbness in civilian life

War messes with your emotions in ways you don’t see coming. For a lot of veterans, it’s a wild swing between two opposite extremes: anger that flares up out of nowhere, and a kind of deep numbness that makes everything feel flat. These moods don’t follow any clear pattern. One day it’s rage, the next it’s nothing at all. That unpredictability just leaves everyone—veterans and their families—feeling stuck and lost.

Anger turns into a knee-jerk reaction. Little stuff—bad traffic, paperwork that drags on, a simple argument—can set it off. The anger feels way out of proportion, like it’s coming from somewhere else entirely. In combat, that kind of hair-trigger anger kept people alive. Back home, it just wrecks relationships and makes daily life tense.

Then there’s the numbness. Things that used to matter—hobbies, friends, even family—barely register. Holidays, birthdays, big wins at work… they just feel empty. Sometimes, even the love you have for your own kids or partner feels distant. It’s not just emotional, either. Physical pleasures—good food, a warm bed, the sun on your face—don’t bring much comfort.

Nobody knows what to expect. Partners feel like they’re walking on eggshells, never sure if they’ll get an angry outburst, cold silence, or a rare glimpse of the person they remember. Veterans, meanwhile, get frustrated with themselves. They want to control these feelings, but can’t. That frustration often turns into shame, and pretty soon, it just feels easier to back away from everyone altogether.

Building trust and intimacy after witnessing violence

Seeing or living through violence really messes with your sense of trust and your ability to open up emotionally. Veterans know this all too well. They often feel stuck in a state of hypervigilance, always scanning the room for threats, even when there’s nothing to worry about. Relaxing? That starts to feel unsafe. Letting anyone in, emotionally or physically, feels even riskier.

Physical closeness isn’t simple anymore. A surprise touch can set off a defensive reaction. Getting emotionally close isn’t much easier—it can feel suffocating, or just flat-out dangerous. The instincts that kept you alive, that push for constant self-protection, end up clashing with the basic need for connection.

And it doesn’t stop at romantic or family relationships. Trust becomes an issue everywhere. Veterans start doubting people’s motives, reading suspicion into simple acts of kindness, or seeing hidden threats in regular social situations. It’s a lonely place to be, and that isolation just makes the gap between them and civilian life feel even wider.

Fixing or forming relationships takes serious patience, from everyone involved. Tiny steps forward deserve recognition, and setbacks need understanding, not blame. A lot of the time, professional help is key—it helps veterans handle those triggered reactions and slowly, piece by piece, rebuild their ability to connect with others in a healthy way.

Neurological Alterations from War Exposure

How chronic stress rewires brain structure permanently

War isn’t just tough in the moment—it leaves a mark that sticks around, deep inside the brain. Picture this: the stress never really lets up, and over time, it actually reshapes the brain itself. Take cortisol, for example. That stress hormone floods the system and starts shrinking the hippocampus, the part of the brain that helps you remember things and keep your emotions in check. Meanwhile, the amygdala—basically your personal alarm system—goes into overdrive and gets bigger, so your brain is always on high alert.

Coming home doesn’t hit the reset button. The prefrontal cortex, which you rely on for making decisions and controlling impulses, just doesn’t fire the way it used to. That’s why so many veterans find themselves struggling to focus, manage their feelings, or even make simple choices that used to be automatic.

Brain scans tell the same story. The outer layer—the cortex—thins out in spots that handle attention and sensory input. The brain’s wiring actually shifts, tuning itself to be better at spotting threats than doing everyday thinking. Stuff like scanning for danger, which once took effort, becomes hardwired and automatic. It’s not something you can just switch off.

Understanding changes in sleep patterns and nightmares

Combat changes the way veterans sleep, and not in a good way. Their nights get chopped up—less REM, more waking up, and their brain just can’t keep a steady sleep rhythm. Falling asleep gets tough, and staying asleep? Even tougher.

Nightmares for veterans hit different. These aren’t just bad dreams; they’re like living the worst moments all over again, right down to the sounds, smells, and even the physical feelings. Sometimes, these nightmares show up more than once in a single night. Sleep starts to feel more like something to fear than something that helps.

Veterans deal with all kinds of sleep problems. There’s sleep apnea, often tied to weight gain or side effects from meds. Insomnia—thanks to always being on high alert—makes it hard to get to sleep or stay there. Night terrors show up too, with sudden jolts of fear in the middle of deep sleep. Some even act out their dreams—kicking, punching, talking—because of REM sleep behavior disorder.

Bad sleep doesn’t just stay in its own lane. It makes everything else harder, especially PTSD. The worse the sleep, the worse the symptoms get, and around it goes—a cycle that’s tough to break.

Addressing substance abuse as coping mechanism

A lot of veterans end up reaching for alcohol, prescription meds, or sometimes illegal drugs just to take the edge off their psychological pain. It usually starts as self-medication—a quick fix to drown out intrusive thoughts, calm that constant sense of danger, or just feel something again.

Alcohol’s a big one. At first, it seems like a lifesaver. It cuts anxiety and lets you sleep. But it doesn’t last. After a while, alcohol wrecks your sleep and drags your mood down even further. The same thing happens with painkillers. Doctors might prescribe them for physical injuries, but soon enough, they’re being used to numb emotional pain too.

There are some common patterns here:

- Alcohol feels like an escape from anxiety and sleepless nights, but it ends up making depression and sleep problems worse.

- Opioids numb pain—physical and emotional—but they’re addictive and mess with your mind.

- Stimulants make you feel awake and sharp at first, but bring paranoia and wreck your sleep.

- Cannabis helps with nightmares and anxiety, but over time, it can mess with your memory and kill your motivation.

The shame around using these substances keeps a lot of veterans from reaching out for help. That isolation just makes everything harder. Real recovery means dealing with both the addiction and the trauma behind it, all at once.

Recognizing traumatic brain injury from combat situations

Traumatic brain injuries, or TBIs, show up a lot in veterans—think explosions, car crashes, or just getting hit hard. These injuries don’t just make things tough physically; they add a whole new layer to mental health struggles. Blast injuries are everywhere, but here’s the tricky part: sometimes the damage hides out for years. You might not spot it right away, but down the road, it messes with your memory, focus, and how fast you think.

Mild TBIs are especially hard to pin down, because the symptoms look a lot like PTSD. It’s a mix of stuff—forgetfulness, trouble paying attention, headaches, dizziness, always feeling tired, or weird sensitivity to lights and sounds. Then there’s the emotional rollercoaster: mood swings, irritability, anxiety, depression. Sleep gets weird too. Some veterans can’t fall asleep, others sleep too much, or barely at all.

Because you can’t see a TBI on the outside, a lot of people don’t realize they have one. Veterans might chalk up what they’re feeling to stress or just having a hard time adjusting, not knowing their brain took a hit. Missing that connection means they don’t get the help or rehab they really need.

And it gets worse with repeated blasts. Each one chips away at the brain—kind of like what you see with athletes who get too many concussions. Processing information, keeping your emotions in check, paying attention—it all starts breaking down. Sometimes, those changes just don’t go away, no matter how much time passes.

Managing chronic pain and physical symptoms of psychological trauma

When it comes to trauma, the mind and body are tied together in ways you can’t really ignore. For a lot of veterans, that means old wounds show up as headaches that won’t quit, tight muscles, stomach problems, or weird pains doctors just can’t explain. The body remembers. Shoulders, neck, and jaw stay tense, like you’re always waiting for the next bad thing. Gut issues flare up because stress hormones mess with digestion. Your heart pounds, blood pressure spikes—like your body’s stuck on high alert. Even the immune system takes a hit, leaving you worn down.

Pain becomes this constant echo of what you’ve been through. It’s not just physical. Every ache drags up something from the past, and that memory makes the pain even sharper. It turns into a loop nobody wants to be stuck in. The usual ways to treat pain don’t cut it because they skip over the mental side of things.

What really helps is an approach that tackles both the body and the mind. That means mixing medical care with therapy designed for trauma. Stuff like yoga, massage, and movement therapy can help veterans feel at home in their bodies again, instead of fighting them. And honestly, recognizing that these aches and pains are real—rooted in psychological scars—makes a huge difference. It opens the door to healing that finally brings mind and body back together.

War doesn’t just leave bruises you can see. It cuts deep into the mind, messing with memories, emotions, and the way people see the world. Veterans know this better than anyone. Combat changes how your brain works, sometimes scrambling thoughts or making even simple things feel impossible. And it’s not just the person who served who feels it—families, friends, whole communities end up carrying some of that weight too. Relationships get rocky. Support systems can buckle.

But here’s the thing: recognizing what’s going on in your head is the first real step toward getting better. If you—or someone you care about—is wrestling with the aftershocks of war, reaching out for help isn’t weakness. It’s actually brave. Therapy, mental health resources, people who get it—these things patch up what war tried to tear apart. The mind can bounce back, even from the hardest stuff. With the right support, finding your way forward isn’t just possible. It’s real.